DEEP DIVE: 25 years on, CERP is restoring the Everglades. But will it be enough?

DEEP DIVE: 25 years on, CERP is restoring the Everglades. But will it be enough?

The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan is often described as a massive effort to “get the water right.”

Unfortunately, CERP isn’t going to “get the water right” right away.

On Dec. 11, 2000, President Bill Clinton signed the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan into law as part of the Water Resources Development Act of 2000. It included 68 engineering projects to “restore, preserve, and protect the south Florida ecosystem while providing for other water-related needs of the region, including water supply and flood protection.”

The suite of projects includes building storage reservoirs, creating flow ways, removing barriers to the natural sheet-flow of water south and restoring natural wetlands across 18,000 square miles in 18 counties.

And we know that even once the largest and most ambitious ecosystem restoration ever undertaken is complete — there will still be work to do in order to “Rescue the River of Grass.”

And we know that even once the largest and most ambitious ecosystem restoration ever undertaken is complete — there will still be work to do in order to “Rescue the River of Grass.”

CERP was originally scheduled to be completed in 30 years at a cost of $8.2 billion. (That’s in fiscal year 2000 dollars, equivalent to more than $13.8 billion now.)

The most recent report to Congress projected completing CERP projects will take until about 2050 at a total cost of about $26.9 billion. That’s due to inflation, changes in some projects’ scope and new project authorizations.

That may be on the optimistic side, because in 2000, when state and federal water managers were contemplating CERP, they weren’t contemplating climate change. And even once adjusting for this, other needs will remain once CERP is done.

The flow of water and money

Paying for CERP projects was designed to be a 50-50 split between the federal government and Florida. Through September 2024, the federal government had spent $3.2 billion and Florida had spent $2.8 billion on CERP construction projects, according to cost-share transparency reporting.

Separate from CERP, the feds have spent about $1 billion on projects that complement CERP but aren’t part of it. For instance, in 2021 the Corps of Engineers completed a 22-year project to reconstruct sections of the channelized lower Kissimmee River to its original, meandering path, which helps (but not completely) clean water entering Lake Okeechobee.

All those projects and all that money are needed to correct, in part, problems caused by the massive development in South Florida.

All those projects and all that money are needed to correct, in part, problems caused by the massive development in South Florida.

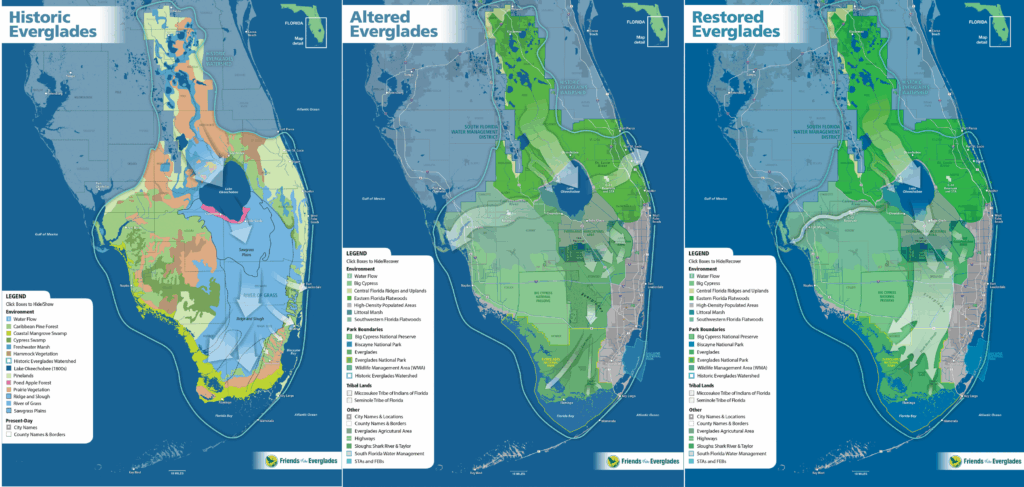

The Everglades once stretched from just south of Orlando, through the Kissimmee chain of lakes, into Lake Okeechobee and all the way south to Florida Bay. Today, the Everglades make up less than half its original size and has lost over 70 percent of its water flow because of urban and agricultural development and the creation of flood control canal systems that drained land for that development.

The timing and volume of water flowing through what once was a “River of Grass” have been thrown out of whack – with the remaining Everglades below Lake O getting parched during dry seasons and the St. Lucie River and Caloosahatchee River estuaries east and west of the lake getting inundated with polluted, blue-green algae-feeding water in wet seasons.

Actual shovels-in-the-dirt progress on CERP projects began slowly, as several years were taken up in initial project authorizations, design, land acquisition, permitting and pilot projects – not to mention the political back-and-forth on some of the projects.

Although only a small handful of projects have been completed at the 25-year mark, the pace has picked up considerably in the couple of years thanks to increased funding on both the federal and state levels.

Where CERP stands right now

Here are the projects that are completed or well on their way:

Melaleuca Eradication: The first CERP project to take root (pun intended) has been an effort to combat this invasive Australian tree that dries out wetlands, alters soil, outcompetes native trees like cypress and slash pine, harms wildlife by destroying natural habitat. The work involves an integrated approach of physical removal, biocontrol insects, herbicides (often to the trunk after cutting) and prescribed burns.

Most large populations have been brought under control, and the focus has shifted to keeping them that way.

C-44 Reservoir and Stormwater Treatment Area: The first CERP construction project to be completed (opening in 2021), the combination of a reservoir and stormwater treatment area is east of Lake Okeechobee along the C-44 Canal connecting the lake and the South Fork of the St. Lucie River. The combined reservoir and STA, with a total price tag $526 million, is designed to reduce nutrient pollution and toxic algae blooms in the St. Lucie River Estuary and Indian River Lagoon.

Unfortunately, the $339 million reservoir has seepage problems, causing it to hold only about 20% of its designed 16.5 billion-gallon capacity. The Army Corps of Engineers is addressing it as a maintenance problem and designing relief wells to manage the water and operating the reservoir at lower levels for now.

C-43 West Basin Storage Reservoir: West of Lake Okeechobee along the C-43 Canal connecting the lake to the Caloosahatchee River, the reservoir was completed in June 2025 at a cost of about $1 billion, about double the original estimate of about $500 million to $550 million.

It’s designed to hold up to 55 billion gallons of water and reduce harmful, toxic algae-producing flows to the Caloosahatchee River Estuary during the wet season while providing much-needed freshwater to the estuary during the dry season.

Herbert Hoover Dike Repairs: The 18-year, $1.5 billion-plus project to rehabilitate the 143-mile earthen dam around Lake Okeechobee was completed in early 2023, three years ahead of schedule. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers project included building 56 miles of seepage barrier, replacing 28 water control structures and improving embankments to protect against flooding.

The improvements also allow for updated water management under the Lake Okeechobee System Operating Manual (commonly called LOSOM) to both send needed water south to the Everglades and Florida Bay in the dry season and reduce the harmful discharges to east to the St. Lucie River and west to the Caloosahatchee River during the wet season.

Picayune Strand Restoration: Completed in late January. Designed to undo the environmental damage done to tens of thousands of acres of wetlands by a proposed but unfinished subdivision, the project included plugging 48 miles of canals, removing 260 miles of crumbling roads and building three major pump stations to restore the ecology of the western Everglades and downstream estuaries, reduce freshwater releases and enhance habitat for fish and wildlife.

Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands Project: The project to rehydrate 190 acres of freshwater wetlands and reduce abrupt freshwater discharges to Biscayne Bay and Biscayne National Park in Miami-Dade County, improving seagrass beds and oyster reefs and increased habitat for seagrasses, fish, alligators and juvenile crocodiles, was completed in December.

Tamiami Trail Bridges: About 3.5 miles of the project to raise portions of U.S. Highway 41 between Tampa and Miami – hence the portmanteau Tamiami Trail – are already in use, with another 6.7 miles scheduled for completion in fall 2026. The stretch of the highway that crosses the Everglades was built on a berm that blocked the water flow of the River of Grass. Impacts included dramatic loss of habitats and the wildlife living in them, wildfires and seagrass die-offs and algae blooms in Florida Bay.

In September ground was broken on a related project, the Blue Shanty Flow Way, to remove 10 miles of berm along the highway.

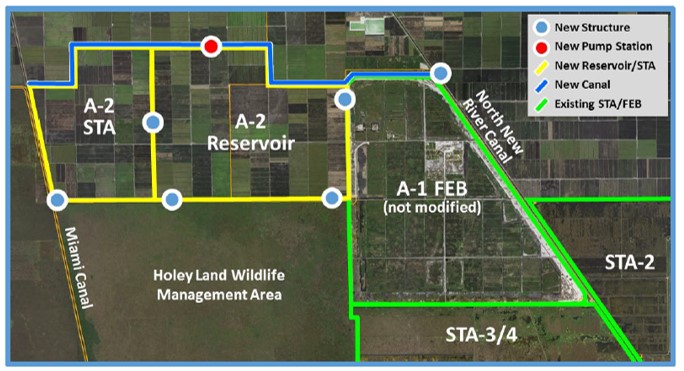

Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) Reservoir: Often called the “crown jewel of Everglades restoration,” the project is designed to reduce harmful discharges from Lake Okeechobee to the St. Lucie River Estuary and Caloosahatchee River Estuaries by storing water from the lake, cleaning it and sending it south to the Everglades and Florida Bay, where the water is needed during the dry season.

With a total size larger than Manhattan Island, the project includes a 10,500-acre reservoir that will be able to store 78 billion gallons of water, a 6,500-acre constructed wetland (a.k.a. stormwater treatment area, or STA) and a system of canals and pumps to move 470 billion gallons of water per year into and through the project and toward the Everglades and Florida Bay.

The first cell of the STA came online in January 2024, with the other two cells following in the next year. The reservoir was scheduled to be completed in 2034, but a 2025 agreement between Florida and the federal government will expedite construction for a 2029 completion.

It took more than 20 years to get revved up, but CERP is now moving at a significant pace. Everyone wants to see this continue; but hurdles lie ahead.

Changing for climate change

Sea-level rise for South Florida is projected to be 10 to 21 inches by 2040 and 21-54 inches and 40 to 136 inches by 2120, according to a 2023 report “Progress Toward Restoring the Everglades” by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

For low-lying South Florida, the threat of climate change-related sea level rise is real and serious. Temperatures and sea levels are already rising, and storms are becoming more severe.

Hurricane Ian in September 2022, for example, caused nearly $113 billion in damage, 156 deaths and widespread flooding across the state’s interior. Researchers at Stony Brook University and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory concluded climate change increased Ian’s rainfall rates by more than 10 percent.

The impact of climate change on CERP projects also is real and serious.

For instance, canals aren’t as able to drain to the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico because sea level rise is pushing back the fresh water. Rising sea levels also push saltwater into freshwater wetlands, causing “peat collapse” and altering coastal mangrove habitats.

With overall temperatures expected to increase by 1.5 degrees Celsius and annual rainfall expected to increase by 10%, both by 2060, the risk of both floods and droughts will increase, making water management more complex.

As a result, changes in climate mean CERP projects will have more water to store, clean and move than was originally planned in 2000.

On the glass-is-half-full side, however: Completed CERP water shortage projects will be an improvement over the current situation, meaning the projects will be something of a hedge against climate change by increasing the ability to better manage water throughout South Florida.

To make sure CERP projects will keep up with climate change, the federal Water Resources Development Act of 2022 authorized a study to focus on factors Everglades restoration has not addressed, especially climate change and flood risk management along the coasts and inland. The effort is expected to get underway this year, could take six to 10 years to complete and is could lead to more construction projects (over more time) in the Everglades to enlarge the capacity of its water infrastructure.

Making sure the federal and state governments will take a serious look at the effects of climate change will require public vigilance because:

President Donald Trump told the United Nations General Assembly in September: This ‘climate change,’ it’s the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world, in my opinion. All of these predictions made by the United Nations and many others, often for bad reasons, were wrong. They were made by stupid people that have cost their countries fortunes and given those same countries no chance for success. If you don’t get away from this green scam, your country is going to fail.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis in May signed legislation removing most mentions of “climate change” from state law, posting on X: “We’re restoring sanity in our approach to energy and rejecting the agenda of the radical green zealots.”

On the other hand, DeSantis has backed Resilient Florida, which has committed over $1 billion in grants to help local governments adapt to climate change.

And in December, DeSantis proposed $1.4 Billion for Everglades Restoration and Water Quality in the state budget for fiscal year 2026-2027.

But we’re not done yet

Will the healthy funding levels continue once CERP is complete?

Lots of people think that once CERP is done, the Everglades will be restored. But it’s not true; as Friends of the Everglades’ “Rescue the River of Grass” campaign has demonstrated, we still need significantly more land south of Lake O both the end discharges to the coasts and send additional clean water south.

Unless we truly “finish the job,” we will have only partially restored the Everglades; we will have fallen short about what the system and all that depend on it truly needs not just to survive — but thrive.