Deep Dive: The growing threat of Vibrio vulnificus

Deep Dive: The growing threat of Vibrio vulnificus

One day — Monday, Feb. 27, 2023, to be exact — Steve Zelenski was in a boat checking stone crab traps on the Indian River Lagoon just west of the House of Refuge near Stuart.

Four days later, the 68-year-old Palm City resident was fighting for his life at the University of Florida Health Shands Hospital in Gainesville.

Officially, Zelenski — who survived but lost four fingertips on his left hand — was diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis, a medical catch-all term for what’s more commonly called “flesh-eating disease.”

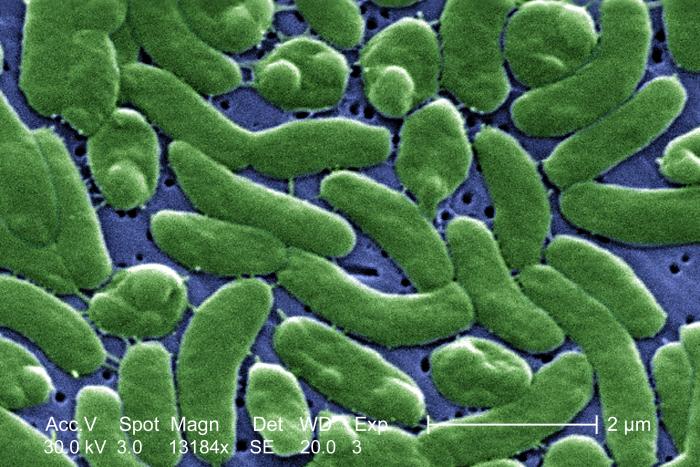

Unofficially, and more specifically, Zelenski is convinced he was infected with Vibrio vulnificus, a potentially deadly type of flesh-eating bacterium found naturally in warm, brackish water.

“It’s most likely the thing that got me,” he told VoteWater recently. “Everything — the symptoms and the timeframe — seems to point to it.”

Infections: Rare but rising

Cases of vibrio infection are rare but on the increase, in large part because of climate change.

As of Dec. 5, Florida has had 33 confirmed cases of Vibrio vulnificus infections and five deaths — two in Bay County and one each in Broward, Hillsborough and St. Johns counties — so far this year, according to the state Department of Health.

Over the last 10 years, Florida averaged about 48 cases and 11 deaths per year, according to FDOH data. In 2024, Florida had a record 82 cases and 19 deaths, a surge health officials linked to flooding caused by back-to-back hurricanes Helene and Milton.

People can get infected with Vibrio vulnificus by eating raw shellfish harvested from warm coastal waters during the summer, particularly oysters. People with open wounds can be exposed to Vibrio vulnificus through direct contact with brackish water. (There is no evidence of person-to-person transmission.)

Zelenski, now 71, doesn’t recall having an open cut when he was dipping his hands into the lagoon water: “I had gloves on. I did what I was supposed to do. I must have had a tiny, little puncture.”

He also remembers the lagoon water that day “was covered with a kind of green slime, like something I’d never seen on the river before. I remember thinking, ‘Thank God the kids aren’t with us,’ because I wouldn’t want them getting into something like that.”

“By Thursday night, I felt like I was getting the flu, violently sick,” Zelenski said, “and on Friday morning (March 3, 2023), I went to a walk-in clinic. They sent me immediately to the hospital, the emergency room.”

By that time, Zelenski said, his left hand (luckily, he’s right-handed.) had turned purple and “was feeling warm.”

At Cleveland Clinic Martin South Hospital in Stuart, Zelenski was told he wasn’t registering a pulse. “They ran a bunch of tests, and the next thing I know, I was being admitted to the ICU (intensive care unit). I was kind of out of it, but I heard that my (left) hand had turned all black.”

He later was transferred to the burn unit at University of Florida Health Shands Hospital in Gainesville, where he would stay for three weeks, return for periodic checkups and receive skin grafts from his elbow to his fingertips.

Zelenski lost the tips of four fingers on his left hand, he said, “and most of the mobility in that hand. But thank goodness they saved my arm. … People treated me excellent. I couldn’t have asked for better care. I consider myself really lucky.”

A Treasure Coast resident since 1978, Zelenski said the area’s waterways “didn’t have the problems they have today.”

Times have changed — and so has the climate

Vibrio and climate change

Climate change plays a role in the increase of Vibrio vulnificus cases in two ways.

First, warming waters create more natural habitat for the bacteria.

According to the Florida Department of Health, the bacteria thrive between 68 and 95 degrees, but it can grow at temperatures up to 105 degrees.

A study titled “Climate warming and increasing Vibrio vulnificus infections in North America” published in March 2023 in the journal Scientific Reports notes that in the eastern United States between 1988 and 2018, Vibrio vulnificus wound infections increased eightfold (from 10 to 80 cases per year); and the northern limit of cases shifted northward about 30 miles per year.

The study’s authors predict that by 2100, Vibrio may be present in every state on the eastern seaboard.

Second, studies suggest that climate change will result in an “increase in the frequency and intensity of hurricanes, tropical storms, and other intense rotating storms,” according to a report titled “Risks to Indian River Lagoon biodiversity caused by climate change” given at the 2020 Indian River Lagoon Symposium.

The study states the increased storminess will cause “an increase in the flux of freshwater” from stormwater runoff.

After the rains, here comes Vibrio

Currently, Vibrio vulnificus is typically found in water with salinity from five to 25 parts per thousand, which is the normal range of saltiness found in estuaries such as the Indian River Lagoon. The bacteria really thrive in water with a salinity ranging from five to 10 parts per thousand, which occurs in the lagoon and the St. Lucie River following heavy rains — especially from tropical storms and slow-moving hurricanes — or massive discharges of freshwater from Lake Okeechobee.

The bacteria can’t handle salinities above 30 parts per thousand, such as open ocean water; but, again, even ocean water, especially near inlets and estuaries, can be diluted by stormwater runoff into Vibrio’s comfort zone.

That’s what happened when Vibrio infections spiked following Hurricane Ian in 2022 and Hurricane Helene in 2024.

(Note: To find out salinity levels in the St. Lucie River and nearby sections of the Indian River Lagoon, check out the Florida Oceanographic Water Ecosystem Surveys. For other sites along the lagoon, check out the Ocean Research and Conservation Association’s Kilroy remote-controlled water data collectors. Also be aware that salinities go up on incoming tides and down on outgoing tides.)

Because the bacteria are a natural part of the coastal ecosystem, there’s no way to get rid of them, Elizabeth Archer, a postgraduate researcher at the U.K.’s University of East Anglia and the study’s lead author, told Forbes magazine, adding, “It’s more about mitigating infections by increasing awareness and improving education about the risk.”

It’s a risk Zelenski is willing to take.

“My doctors don’t want me out on the water yet,” he said. “But as soon as I get clearance, I’m getting back out there.”

IMPORTANT: The Florida Department of Health warns that people who are immunocompromised (e.g. chronic liver disease, kidney disease, or weakened immune system) should wear proper foot protection to prevent cuts and injury caused by rocks and shells on the beach.

Tips from the FDOH for preventing Vibrio vulnificus infections

- Do not eat raw oysters or other raw shellfish.

- Cook shellfish (oysters, clams, mussels) thoroughly.

- For shellfish in the shell, either a) boil until the shells open and continue boiling for 5 more minutes, or b) steam until the shells open and then continue cooking for 9 more minutes. Do not eat those shellfish that do not open during cooking. Boil shucked oysters at least 3 minutes, or fry them in oil at least 10 minutes at 375 degrees.

- Avoid cross-contamination of cooked seafood and other foods with raw seafood and juices from raw seafood.

- Eat shellfish promptly after cooking and refrigerate leftovers.

- Avoid exposure of open wounds or broken skin to warm salt or brackish water, or to raw shellfish harvested from such waters.

- Wear gloves and other protective clothing when handling raw shellfish.