DEEP DIVE: What’s killing lagoon dolphins?

DEEP DIVE: What’s killing lagoon dolphins?

Three bottlenose dolphins recently found dead in the Indian River Lagoon appear to have died of an unusual — and alarming — cause.

News reports indicate the three dolphins tested positive for bird flu; and results are pending on other dolphins found dead within the past month to see if they were similarly afflicted.

Some 1,000 dolphins live in the 156-mile long lagoon; deaths aren’t uncommon. But the biggest danger to these creatures isn’t birds — it’s us.

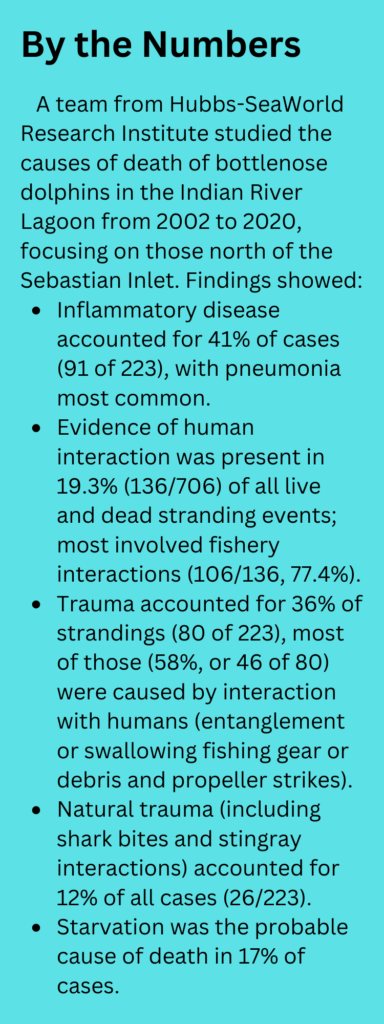

A 2023 study by a team from Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute found many bottlenose dolphins in the lagoon choke on, or get tangled up in, fishing lines, lures and other fishing gear. “Fishing gear interactions — entanglement and ingestion — were the most common anthropogenic (translation: caused by humans) trauma,” according to the study published in the journal Wildlife Disease.

Other dolphins starve to death, most likely because years of toxic algal blooms in the lagoon — caused by polluted runoff from development along the waterway — have wiped out seagrass beds, drastically reducing the number of creatures that eat the grass and are, in turn, eaten by dolphins.

Loss of seagrass and the fish that need it for habitat increases the chances of entanglements. According to the study, “Dolphins may come in contact with fisheries while in pursuit of similar target species, therefore as lagoon fish populations are depleted and ecosystem health declines, high-risk fishery interaction behaviors and associated injury or mortality may increase.”

The most common cause of death — respiratory disease — can also be linked to humans: The dolphins that don’t starve because of algal blooms are left emaciated and more likely to die from illness.

Dolphins are susceptible to respiratory diseases, said Wendy Noke Durden, research scientist and co-director of the Marine Mammal Research and Rescue Program at Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute in Melbourne Beach, “because they breathe through their blowholes at the surface of the water where they come in contact with pollutants. Pneumonia is very common.”

Dolphins are susceptible to respiratory diseases, said Wendy Noke Durden, research scientist and co-director of the Marine Mammal Research and Rescue Program at Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute in Melbourne Beach, “because they breathe through their blowholes at the surface of the water where they come in contact with pollutants. Pneumonia is very common.”

Also, those starving dolphins are more likely to interact with fishermen and their tackle.

“We know that dolphins will take more risks if they’re emaciated,” said Durden, an author of the Hubbs-SeaWorld study. “They’ll feed more readily around fishers.”

As if all that weren’t enough, the study noted that lagoon dolphins are “immunocompromised,” meaning their immune systems have been weakened and are less able to fight off infectious diseases and cancer.

“There’s no answer to why lagoon dolphins are immune-compromised,” Durden said, “although we know there are high levels of mercury in the habitat.”

Dolphins in the lagoon have been subjected to four “unusual mortality events”: in 2001 and 2008, both for unknown reasons; in 2013 because of toxic algae; and from 2013–2015, caused by the dolphin morbillivirus.

The 2013 UME was the worst, killing 77 dolphins as well as numerous manatees and pelicans.

Cruel, cruel summer

For several reasons, significantly more deaths occur during the summer.

First, dolphins tend to calve from late spring to early fall, and baby dolphins are more susceptible to disease.

Also, algal blooms are much more prevalent in the summer and may lead to low-oxygen conditions and fish kills, which reduces prey.

Finally, high summer water temperatures in the lagoon can lead to stress and compromise dolphins’ health.

The study focuses on the northern section of the lagoon from the Sebastian Inlet to the Ponce Inlet, the area where the Hubbs-SeaWorld team conducts rescues and where, according to the study, 88% of the strandings occur. A similar rescue team from Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute near Fort Pierce responds to strandings in the southern lagoon from Sebastian to the Jupiter Inlet.

Steve Burton, director of Harbor Branch’s Marine Mammal Stranding and Population Assessment Team, said HBOI hasn’t conducted a dolphin mortality study similar to Hubbs-SeaWorld’s. Nic Mader, who studies dolphins in the lagoon from Stuart to Jupiter as a field biologist with the Dolphin Ecology Project, said she hasn’t personally seen entangled dolphins, but it “is a definite problem. If you just think of all the recreational fisherman out there and all the line cutting. It’s a travesty.”

Staying close to home

Earlier research by Harbor Branch scientists has shown lagoon dolphins tend to stay in the lagoon, and dolphins in the ocean tend not to enter the lagoon.

The 1,000 or so dolphins in the lagoon are divided into six distinct groups, and they tend to stay in their group’s area. On average, dolphins ranged 17 miles during the course of the study; one ranged only about 8 miles over 97 days.

The limited range is a concern, because dolphins tend not to move away when their areas become dangerous from either algal blooms or large numbers of fishermen.

Put all that together, and survival is particularly tough for the dolphins that call the lagoon home.

What can be done to help them out?

The simplest answer is for fishermen to not leave gear in the water.

In 2024, 16 dolphins died from entanglements, Durden said. “That’s a significant number for the area. We’re seeing an increase for sure.”

In the Banana River section of the lagoon, run-ins with humans is the leading cause of dolphin deaths.

“The more people fish, the more dolphins get entangled,” Durden said. Fishing lines are the threat that keeps on threatening.

“Monofilament and braided fishing lines take hundreds of years to disintegrate,” Durden said.

Not many dolphins get entangled in “active” fishing gear, Durden said, “but it’s still important that, if you see dolphins while you’re fishing, to reel in your gear.”

Durden said a separate study found that dolphin calves learn hunting techniques from their mothers.

“If Mom is hunting around docks and piers where fishers tend to be,” she said, “chances are her calves will, too.”

Keeping fishing gear out of the lagoon will help not only dolphins “but all the wildlife living there,”

Durden said. “The public can be our greatest ally in saving lagoon wildlife.”

World-wide problem

World-wide problem

The problem isn’t limited to dolphins or the Indian River Lagoon. The California-based Marine Mammal Center estimates that worldwide 300,000 whales, dolphins and porpoises die every year from entanglement in ocean trash and fishing gear. And for every entangled whale reported, approximately 10 more go unreported.

And fishing gear isn’t the only culprit: “Dolphins are curious,” Durden said. “We’ve seen them entangled in everything from a bungee cord to a Speedo. And lots of dolphins have trash and debris in their stomachs. So we need to keep trash of all kinds out of the lagoon.”

The Hubbs-SeaWorld study noted that collisions with boats — particularly propellers — accounted for just 2.2% of cases. But that doesn’t mean boat strikes aren’t a concern.

“We have many mangled fins,” Mader said, adding that some of the injuries are from monofilament lines, but a lot are caused by boat strikes.

“We have a dolphin named Rippy,” Mader said (Yes, researchers become so familiar with dolphins in the lagoon that they’re given names), “whose fin is completely sideways down due to propeller strike, along with others that are severed in different places.”

An area known as the Crossroads — where the lagoon, the St. Lucie Inlet, the Manatee Pocket and the St. Lucie River all intersect — “is such a dangerous place, not only for dolphins and manatees but boaters,” said Mader. “It’s just awful. Boats speed through like crazy, even on weekdays when it’s not as busy as weekends. Something has to be done. … And dolphins LOVE to feed in the mouth of the Manatee Pocket.”

So the simplest thing we can do to save Indian River Lagoon dolphins is keep trash — fishing gear in particular — out of the water. The not-so-simple — but ultimately doable —thing is to keep out pollution.

How to help

- If you’re fishing and see dolphins or manatees in the area, reel in your gear.

- Anytime you’re at the beach or on the lagoon or ocean, dispose of trash to keep it out of the water.

- Recycle fishing line.

- Remove any fishing line (Watch out for hooks!) you find in the water.

- To report a dolphin or manatee in distress, entangled, or stranded, call the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission hotline 888-404-3922.

- Take photos and/or video to help the rescue team find and document the animal.