Everglades restoration could fall short – here’s what to do about it

Everglades restoration could fall short – here’s what to do about it

We hate to say, “We told you so.” But we told you so.

For years, first as Bullsugar.org and now as VoteWater, we’ve advocated for two key points:

- We need more land south of Lake Okeechobee to store water and send clean water south to the Everglades.

- Florida must crack down on polluters.

Then last week the National Academy of Sciences issued a report on the progress of Everglades restoration, suggesting that unless these points are addressed, restoration efforts could stall, the flow of clean water to the Everglades could be constrained and discharges to the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee estuaries might not be cut as much as promised.

Can science save the day? Or will Florida officials finally seek out solutions they should have been pursuing all along?

Overall, the tone of the ninth biennial “Progress Towards Restoring the Everglades” was upbeat, noting that implementation of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, or CERP, “is occurring at a remarkable pace… thanks to record funding levels.”

That’s great news.

But two big challenges loom: Water quality and climate change. On climate change, rising temperatures and sea levels pose significant obstacles; more saltwater intrusion and evaporation will require better planning and more flexibility as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and South Florida Water Management District adapt to changing conditions.

Politically, water quality might be a tougher nut to crack.

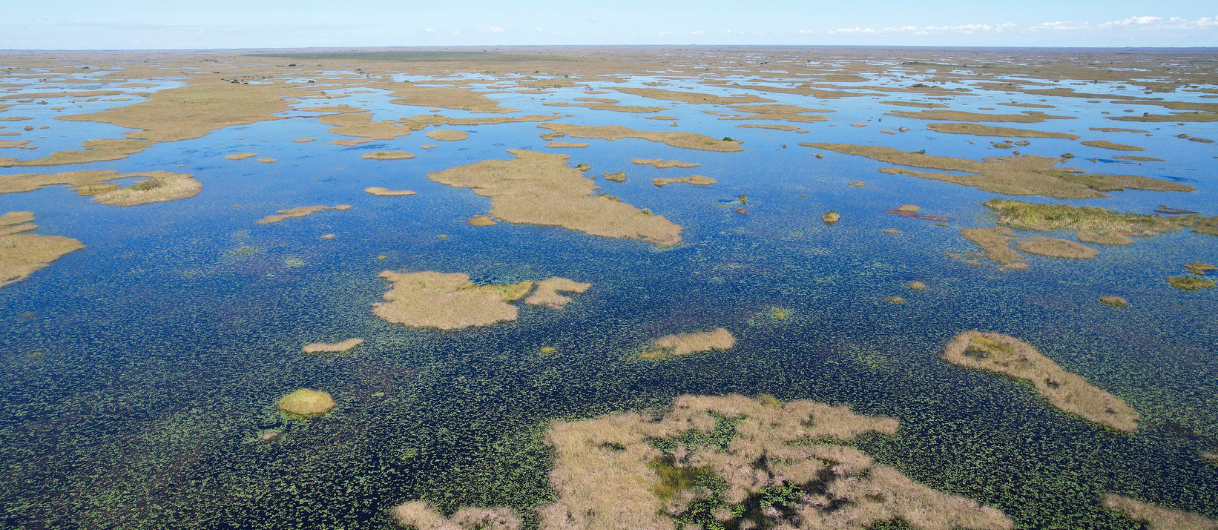

Looming large in the discussion is the “water quality based effluent limit” or WQBEL, a legal requirement limiting the amount of phosphorus in water sent from man-made wetlands south of Lake Okeechobee (called “stormwater treatment areas” or STAs) to the Everglades.

The problem, according to the report, is that water coming into these man-made wetlands is so chock full of phosphorus the vegetation can’t remove enough of it to meet the WQBEL.

Water that doesn’t meet the WQBEL cannot legally be sent south to the Everglades.

To fix this, the report suggests one of three strategies: improve the phosphorus removal efficiency of the STAs — if possible; “increase the footprint (surface area) of the STA” — in other words, acquire more land for water storage; and/or “decrease the upstream phosphorus loading entering the STA” — by cracking down on polluters.

What about the soon-to-be-built EAA reservoir and its adjacent STA? Won’t that save the day?

Nope. In fact, the reservoir’s benefits might fall short of what we were promised if those man-made wetlands continue to have trouble.

If the reservoir project footprint, which includes the new STA, had been larger — as we advocated — it might not be a problem. But Florida policymakers allowed the EAA Reservoir to be shrunken from the originally envisioned 60,000 acres to about 17,500 acres — due largely to pressure from the sugarcane industry. Then the reservoir’s new STA was sized on the assumption that excess capacity in existing STAs could be used to treat water from the reservoir before flowing it south.

If those STAs can’t meet the WBQEL, that capacity won’t be available.

And if not, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “will limit operations of, and thus the benefits provided by, the EAA Reservoir,” according to the report.

The reservoir “may only be operated to flow the amount of water that the new EAA (STA) alone can treat” to required standards.

Meaning: the reservoir won’t take as much lake water as originally promised. Water sent south to the Everglades could fall short of what was originally promised.

And Lake O discharges to the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee estuaries? They’ll be cut — but nowhere near as much as we were told.

This, coupled with other scientific concerns about whether the EAA reservoir itself will perform as advertised, suggest that even after all this time and all this money, clean-water advocates are going to have to settle for less. Again.

The authors of the report seem optimistic that improved science and additional layers of scientific oversight can fix these problems.

Maybe. But what we need most are political leaders with backbone. Officials who’ll push to acquire more land to create wetland marshes even if there aren’t many willing sellers. Regulators who’ll crack down on pollution despite the inevitable howls from polluting industries.

Everglades restoration is too costly — and too important — to settle for less.