We Asked For Toxicology Screens. We Got Smoke Screens.

We Asked For Toxicology Screens. We Got Smoke Screens.

“How toxic is too toxic?” Don’t ask.

A year ago, Congressman Brian Mast questioned the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers about their role in tracking toxicity and warning affected communities when cyanobacteria blooms occur. His questions highlighted what has historically been an unacceptable toleration for coastal communities’ exposure to health threats from Lake Okeechobee discharges.

Things are different now. This month the Corps did what Florida state health departments have been reluctant to do: Warn boaters and fishermen to avoid cyanobacteria blooms on Lake Okeechobee. Then the Corps admitted that they consider discharges from the lake to be toxic. But where does that leave us, the thousands and thousands who were exposed to the toxins for years?

Last summer a study hosted by Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute recruited 70 people living along the St. Lucie River to provide samples of blood, urine, and nasal swabs to test for microcystin, the toxin produced by cyanobacteria.

The tests came back positive. All of them. Preliminary results revealed that 100% of subjects presented with “detectable levels” of microcystin in their noses. That means the toxins weren’t just in the water. The air we breathed contained microcystin too.

Individual test reports weren’t offered to participants and no further information on the results of the blood or urine tests emerged. So when Bullsugar received a call from a participant asking for help getting the same test from a private physician, we thought, how hard could it be?

She knew she was “a likely candidate for dangerous exposure.” She lived in Palm City, where she could see–and smell–the cyanobacteria blooms spewing from the lake. Her eyes burned during the discharges, and it was a little more difficult to breathe. She didn’t know how long she’d have to wait for the bureaucratic red tape to lift on last year’s study, so she was willing to spring for her own test to see how much of the cyanotoxin was still in her system.

She didn’t count on the goose chase that followed, and neither did we.

Our question seemed simple: What sort of test could she request from a private doctor?

Every phone call and email message led to another dead end. The county and the state passed us from person to person, department to department, only to receive carefully ambiguous or shockingly uninformed answers. It became clear that the agencies most responsible for handling a health crisis were just as in the dark as the rest of us.

A recent public records request of Florida Department of Health emails revealed that the runaround we got wasn’t unique. In fact the agency struggled to answer any questions, prompting one Martin County resident to refer to the lack of response she got as “Florida’s Flint–ignoring a problem because it is too scary and difficult to deal with.”

The official FDOH website, where many callers were directed, vaguely warned against exposure and made only passing reference to the most serious health concerns associated with toxic blooms.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection seemed more interested in concealing the extent of the threat than warning the public, testing the fringes of the blooms where toxins should be lowest, in conditions and at times when concentrations should be less detectable, and then reporting low levels of toxicity. The people of Florida deserve better warnings.

Our caller is still trying to find answers from private doctors, who themselves are frustrated with public agencies’ responses. And their frustration doesn’t end at their inability to address questions regarding an individual patient’s exposure.

Why have the studies and testing we’ve seen come from privately-funded organizations and nonprofits, and not government agencies? It was Harbor Branch and Florida Gulf Coast University that acted to explore the airborne health risks of microcystin. It was the Guardians of Martin County that funded an O.R.C.A. study to measure microcystin levels in fish to see whether it was safe to eat from local waters.

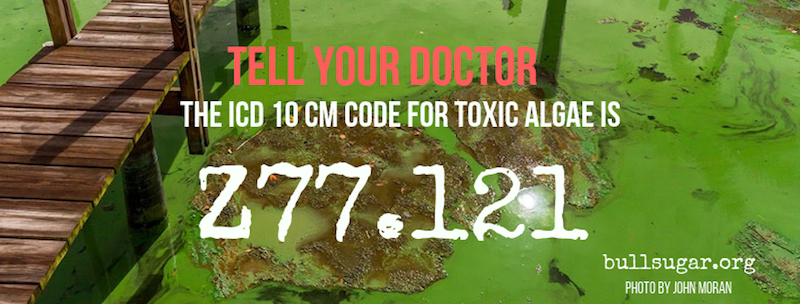

Last month it was the Calusa Waterkeeper who held a public health alert summit to talk about how to protect ourselves from toxic blooms. One critical piece of advice: Tell your doctor and help spread the word within the medical community about the newly designated ICD 10 CM code for health impacts related to toxic algae: Z77.121.

This code, part of an international classification of disease used by physicians and other healthcare providers, can help to ensure we have an accurate database of reporting.

Why isn’t this information plastered across government websites? Holly Rauen captured the holes in agencies’ accountability in this short video clip.

As Dr. Larry Brand pointed out, Floridians won’t know the full extent of long-term exposure to these toxins for years. The woman who asked for our help doesn’t know how long she’ll have to wait, or whether symptoms of illness will be her first clues about the consequences of living within breathing distance of the blooms. She deserves better answers. We all do.