Who Paid the Price for Sugar’s Record Year?

Who Paid the Price for Sugar’s Record Year?

Florida’s sugar industry just posted one of the best years in its history, even as the Everglades and virtually everyone in South Florida suffered one of the worst. It’s not a coincidence. Managing water in Florida means picking winners and losers. When there’s a drought, losers go thirsty. When it rains, losers drown. In 38 years of public records, sugar has yet to lose.

The Everglades lost on both sides in 2017. Barely a trickle flowed south into Everglades National Park and Florida Bay for the first five months of the year. River mouths dried up, brackish estuaries became saltier than the ocean, seagrass meadows collapsed. Guides reported miles of lifeless, stinking water where some of the most productive shallow fisheries had thrived for years.

The Caloosahatchee and its massive Gulf coast estuary and the seagrasses that support it weren’t getting enough freshwater, either. But locks from Lake Okeechobee stayed closed, holding water back for the only customer getting all it needed. Even as residents around the region faced watering restrictions, sugarcane fields stayed wet all spring. As South Florida went brown, all signs in the Everglades Agricultural Area pointed to a record sugarcane crop.

Meanwhile the Florida state legislature delivered more good news to the industry, rewarding its relentless lobbying campaign to block relief for the Everglades and estuaries by forcing the EAA reservoir to use public land and suspending eminent domain for the project. That limited the reservoir’s capacity to send more water to the parched Everglades and absorb discharges like the surge that wiped out the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie estuaries a year earlier.

Then a foot of rain ended a six-month drought almost instantly, leaving the sugar growers with more than 100 billion gallons of water they wanted off their fields, because sugarcane can’t thrive in standing water for even a few days. Off it went, overwhelming treatment marshes and Water Conservation Areas, flooding into the Everglades, drowning everything that couldn’t swim, trapping the rest on a handful of tree islands without enough food to survive. Then-FWC Commissioner Ron Bergeron said at the time, “This event is so catastrophic that if we don’t act, we may not have anything left to save.” We’ll never know how much wildlife was sacrificed for the 2017-18 sugarcane crop.

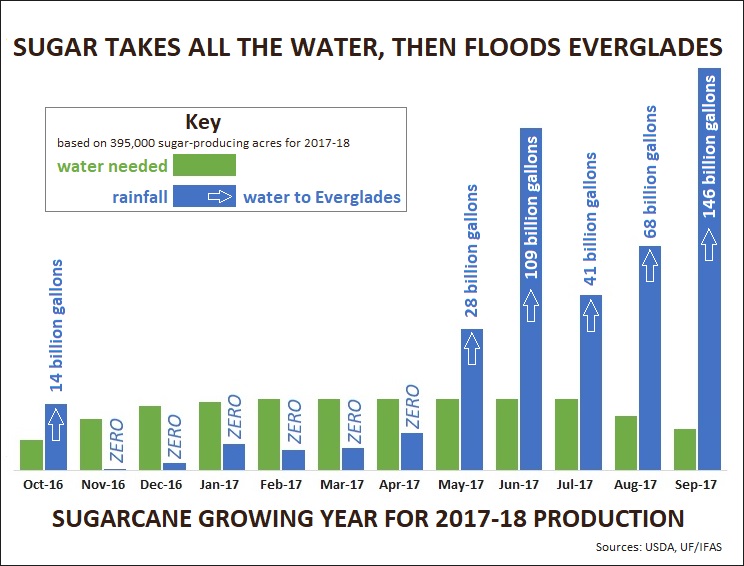

The chart below traces the water that the industry’s 395,000 sugar-producing acres got, needed, and dumped during the 2017-18 growing year. Water levels stayed high as the industry needed to flush roughly 250 billion gallons of runoff into the Everglades between May and August. Then the hurricanes came.

The estuaries had no chance. Lake Okeechobee had been rising all summer. The sugar industry didn’t need any more water–its runoff was already filling the flood control system. When Irma sent lake levels above the dike’s safety threshold there was nowhere else to put the water, so it went to the rivers. In the St. Lucie, lingering oyster populations that somehow survived the Toxic Summer of 2016 died off completely. The Caloosahatchee sent black water deep into the Gulf, pushing the estuary miles offshore.

While continuing to pump runoff into the Everglades and into the lake–even as USACE conducted daily inspections for signs of a breach–sugar executives claimed their lucky run was over. They asked for almost $400 million in hurricane relief–more than half the total value of their annual crop.

Doubts about the claim surfaced in December when a commodities trader told Reuters his firm expected strong production from Florida’s sugar industry, saying “I don’t think the hurricane had any impact.” Last week USDA confirmed it: the industry’s production of 1,992,000 tons was third-best in the past 15 years and seventh-best since USDA records began in 1980. Even better, the crop yielded 5 tons of sugar per acre–fifth-best on record. If 2017-18 turned out to be a sugar yield for the ages, it still didn’t stop the industry from keeping its hand out for federal aid. Add its reported $382,603,397 insurance claim to the annual take, and Hurricane Irma might have given the sugar industry its best year ever.

Meanwhile the collapse of Florida Bay continues. Clearing water in the St. Lucie has revealed a sprawling moonscape where grass flats used to be. The Caloosahatchee is in crisis. And phosphorous levels on Lake Okeechobee are spiking with resuspended nutrients stirring to the surface after decades of accumulating in bottom sediment, providing far more fuel for toxic algae than in 2016. The stage is set for more cyanobacteria blooms linked to cancer, neurological diseases, and liver failure in waterside communities. Florida’s water managers picked one winner and a host of losers last year, and their decisions will be felt for years to come.

The sugar industry is a legitimate stakeholder in South Florida’s water management system, and no one seriously questions its right to protection. But we should question, at the highest levels, what and who should have to die for its profit?