VoteWater Deep Dive: What if the seagrass keeps dying?

VoteWater Deep Dive: What if the seagrass keeps dying?

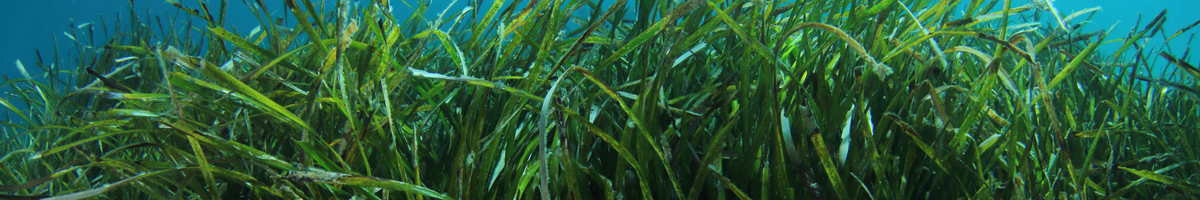

The widespread die-off of seagrass in Florida ought to be front-page news.

And last fall it was, as Gannett’s Florida Today issued a blockbuster report on how seagrass appears to be receding in every coastal corner of Florida, at levels seldom seen before.”

The numbers are staggering:

- The Indian River Lagoon lost 58% of its seagrass area since 2009, more than 46,000 acres. This was a huge factor in the record number of manatee deaths that occurred in 2021, and the near-record pace this year.

- Tampa Bay lost 13% of its seagrass, more than 5,400 acres, according to the Southwest Florida Water Management District, while Sarasota Bay lost 18% of its seagrass between 2018 and 2020, more than 2,300 acres.

- Since 2018, Charlotte Harbor lost 23% of its seagrass, some 4,500 acres. Nearby Lemon Bay also lost about 12% of its seagrasses since 2018, according to the Southwest Florida Water Management District.

- In South Florida, hot and salty conditions helped trigger the demise of as much as 10,000 acres of seagrass in western Florida Bay.

The main culprit: Poor water quality — a situation that can get even worse as seagrass dies off.

Some 2.5 million acres of seagrass is thought to remain in Florida’s nearshore waters; it remains a key to the state’s biological diversity and economic vitality, as every 2.5 acres supports about 100,000 fish, 100 million invertebrates like worms and clams and creates up to $10,000 in economic activity.

The loss of this invaluable resource is a cascading crisis that needs to be high on the state legislature’s agenda in 2023. Lawmakers need to first stop the bleeding by rejecting measures that could make the situation worse – such as the “seagrass mitigation banking” bill likely to be resurrected after failing to advance in each of the past two sessions

But the tougher task involves improving water quality. In a state where “non-point” pollution dumps so many nutrients into our water, where aging infrastructure damaged by storms like Hurricane Ian can spill millions of gallons of raw sewage into already-compromised waterways, it’s a huge mountain to climb.

But with the Environmental Protection Agency’s determination earlier this month that Florida must toughen water quality standards to meet Clean Water Act standards and protect citizens’ health, lawmakers have a key opportunity to make Florida into a leader on water quality standards — rather than a laggard falling ever behind as seagrass, manatees and ultimately Florida’s way of life dies off.

Death spiral

Florida counts seven species of seagrass: the most common is shoal grass (Halodule wrightii), dubbed a “pioneer species” due to its ability to spread quickly and stabilize bottom sediment. Oher species include Johnson’s seagrass (Halophila johnsonii), a threatened species found only on the southeast coast of Florida;; manatee grass (Syringodium filiforme); turtle grass (Thalassia tesudinum); paddle grass (Halopila decipiens); star grass (Halopila engelmannni); and widgeon grass (Ruppa maritima).

Seagrass beds are vital to water quality and sediment control; their root systems hold down sediment and prevent underwater erosion. Above ground, their nodes and blades help trap and settle sediment and reduce turbidity. The water is clearer — and this is vital to seagrass survival, in that low light caused by turbidity is a major reason seagrass dies.

And when it does it can trigger a death spiral — less seagrass equals more turbidity, which equals even less seagrass.

Seagrass also plays a critical role in capturing pollutants like carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus. But when there’s too much of these nutrients in the water — due to sewage spills, septic tanks or runoff — it can feel algal blooms, which shade the seagrass, killing it. There’s less seagrass to take up the nutrients, making even more available to blooms, leading to even less light penetrating the water column.

Once again: the death spiral.

More stressful conditions for seagrass means less seed production and lower germination rates.

And when the seagrass goes, so goes the marine life that relies upon it.

All seagrasses growing in Florida are consumed by manatees; and the decline of the grasses has triggered a catastrophe for the sea cows.

In 2021 1,101 manatees died, a record; the pace has slowed only slightly this year, with the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission reporting 760 deaths through Dec. 2. More than half — 342 — occurred in Broward County, home to a stretch of the Indian River Lagoon that’s proven to be ground zero for Florida’s manatee die-off, as well as sea grass die-off.

State officials have announced they will continue to feed romaine lettuce to the famished manatees. It’s a temporary solution that appears well on its way to becoming permanent. For “fixing” the problem would require restoring seagrasses in areas where it once thrived. And that’s far easier said than done.

Tough to grow, harder to keep alive

It’s not easy to grow seagrass. Widgeon grass is the easiest to propagate, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission; other key species are very difficult to grow and keep alive for any length of time.

Traditionally, seagrass has been planted by hand using peat pellets, coconut-fiber mats or peat pots. One recent study evaluated 1,786 restoration sites and reported seagrass survival rates of 37% overall. The figure was higher for large restoration sites; plantings tend to fare better on a larger scale.

But very few restoration projects have evaluation periods longer than five years. In other words, 7 or 9 years down the line, is the newly planted seagrass still living? There’s little data to say one way or the other.

There have been some success stories. Between 1988 and 2014, aggressive efforts to cut nutrient pollution in Sarasota Bay led to seagrass covering more acreage than in 1950.

Then more than 800 million gallons of insufficiently treated sewage released into the bay, higher rainfall totals and population growth that taxed aging infrastructure shifted everything into reverse — and most of the increased seagrass coverage disappeared.

Tampa Bay lost 46% of its seagrass between 1950 and the 1980s until measures to reduce nitrogen helped the beds rebound; by 2015 the bay had more than 40,000 acres of seagrass, surpassing the 1950 total.

But over the past four years the bay has seen a “significant” decline, losing as much as 6,300 acres.

Seagrass loss isn’t just a problem in Florida; globally, seagrass is lost at an estimated 2-5% per year.

The only way forward involves zealously protecting the seagrasses we have left.

Don’t bank on the ‘mitigation bank’

Yet as another legislative session approaches, legislators appear poised to do more harm than good.

During the 2022 session, Rep. Tyler Sirois, R-Merritt Island, and Sen. Ana Maria Rodriquez, R-Doral, sponsored bills to create seagrass mitigation banks, an idea initially proposed by Rep. Toby Overdorf, R-Stuart, during the 2021 session.

The proposals would have created “banks” on publicly owned submerged lands where seagrass is planted; developers or private individuals who wanted to destroy seagrass would need to purchase credits, essentially financing the planting of new grasses to offset the destruction of existing grasses.

The new plantings would need to take place in the same watershed, but as noted by Lindsay Cross — then water and land policy director for Florida Conservation Voters, now the elected representative for Florida House District 60 — in a January op-ed, “The science behind transplanting is still evolving, but the success rate worldwide is dismal, hovering around 37%. Even in Florida, where biologists have worked for decades honing the best techniques, research shows that transplanted grass is not as thick as natural beds.”

“In short, destroying 100% of seagrass in one area with a small chance that it will regrow somewhere else is a gamble we shouldn’t be taking — especially now,” she wrote.

But the most important thing legislators can do in this upcoming session is update Florida’s water quality standards to meet EPA guidelines.

In a Dec. 1 letter, the EPA said current Florida criteria for 40 toxic pollutants fails to meet Clean Water Act requirements, does not reflect the latest science and must be amended.

The EPA also determined Florida — which last updated its human health criteria for surface waters in 1992 — doesn’t even regulate 37 toxic pollutants which can have an effect on human health.

The Legislature needs to act, and boldly, this session.

Shouldn’t Florida be a leader when it comes to water quality standards. In a state so dependent on water for recreation and economic prosperity, why does it take the federal government to tell Florida to fix the problem?

Florida was once known worldwide for its diverse natural waterways. Now we’re becoming known for poor water quality, dying manatees — and dead seagrass.

Floridians deserve better. And VoteWater will be watching our legislators — and supporting those who lead the way.