Special Report: 10 years after the ‘Lost Summer’ of 2013, what’s changed?

Special Report: 10 years after the ‘Lost Summer’ of 2013, what’s changed?

Ten years ago today, we were in the eye of the storm.

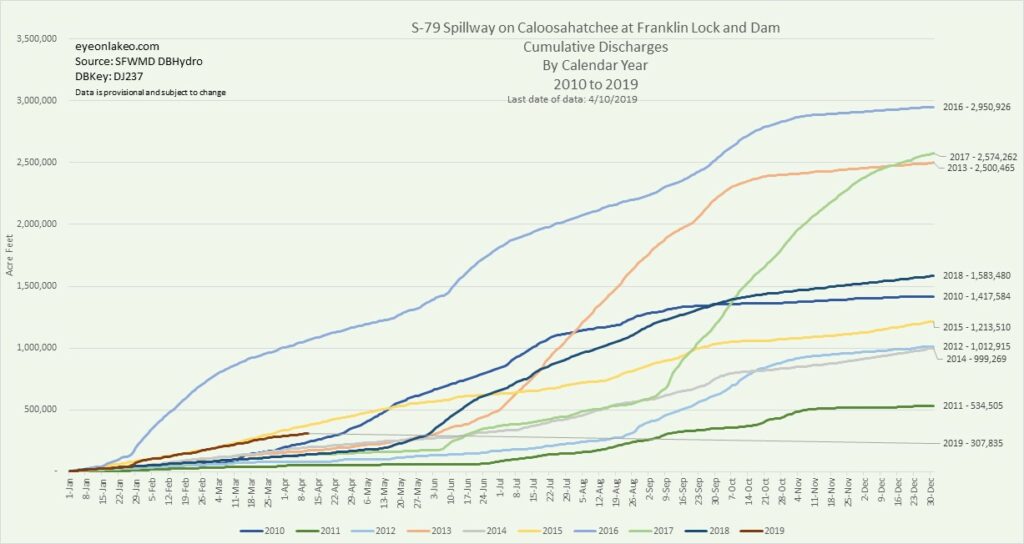

The discharges from Lake Okeechobee to the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers had begun May 8; by early August 2013 the “Lost Summer” was in full swing, with discharges from Lake Okeechobee crushing Florida’s east and west coasts. By the time the gates finally closed on Oct. 21, the Caloosahatchee would see 815 billion gallons of water from the lake and local basin runoff. Plumes of brown water sullied Lee County beaches that summer, and the mayors of five Lee County municipalities joined forces to demand better policies and new projects.As bad as things were on the west coast, they were worse to the east.

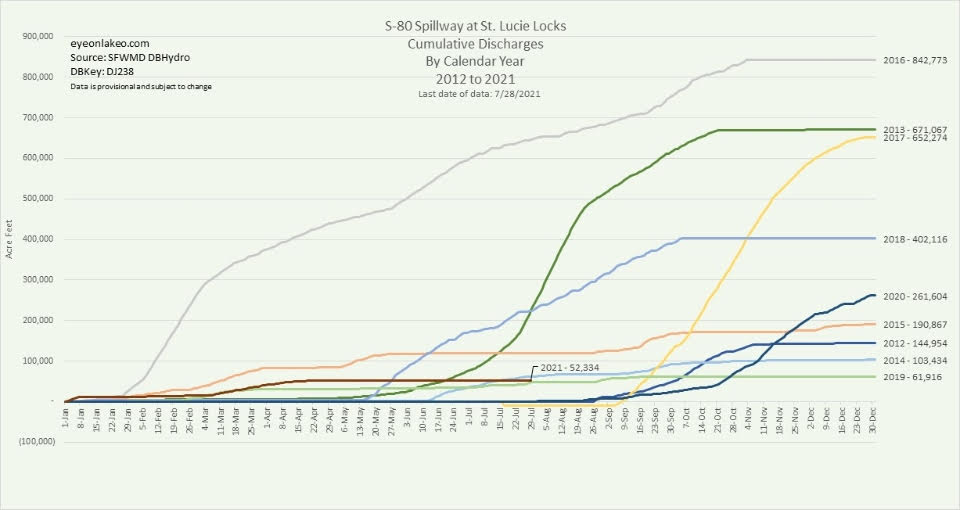

In a Sept. 8, 2013 article on the crisis, the New York Times described the water in Stuart as “about as inviting as someone else’s filthy bath water.” For 24 straight days at one point, more than 5,000 cubic feet of water per second — 2.2 million gallons per minute — poured into the St. Lucie Canal, headed for Stuart. Ultimately more than 671,000 acre-feet of water — 218 billion gallons — from the lake and local basin would inundate the estuary, a massive amount for an estuary so much smaller than the Caloosahatchee. With the water came some 54 million pounds of suspended sediment, 3.5 million pounds of total nitrogen, 433,000 pounds of total phosphorus — and blue-green algae from the lake.

Indeed, the 2013 discharges marked the first time toxic blue-green algae bloomed in the St. Lucie on a massive scale. The Martin County Health Department warned residents to avoid contact with the water. Seagrass died off, anglers stayed away; business at some marinas ground to a standstill.

And the nasty water was accompanied by an increasingly foul mood among the public.

Thousands of furious Martin County residents packed a rally at the St. Lucie locks to demand action. Then-Gov. Rick Scott showed up, but the chants turned angry when Scott failed to acknowledge the concerned residents.

St. Lucie and Martin counties declared a state of emergency in early September. In October a local delegation traveled to Washington D.C. to discuss the crisis with federal lawmakers; Jacqui Thurlow-Lippisch, then a Sewalls Point Commissioner, said in an email to friends and supporters that though the volume of discharges had been ratcheted down and salinities were rising, “the oysters are 100 percent dead and seagrasses down about 60%.”

At the state level, then-Sen. Joe Negron called on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to cede control of Lake O releases to the state of Florida and organized legislative hearings in Stuart to address the problems. Following the hearings, Negron promised “measurable progress in reasonable time.”

And here we are 10 years later. How far have we come?

In fact, the discharges of 2013 would be eclipsed in 2016, when 275 billion gallons from the lake and basin runoff pummeled the estuary, along with an even worse algae crisis than 2013. Two years later, the discharges of “Toxic 2018” fed red tide on all three Florida shorelines; that same year, 90 percent of Lake O was covered in algae by early July.

Today, Lake O stands at over 15 feet, and blooms cover large portions of the lake. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has indicated high-volume discharges to both estuaries could begin if or when the lake hits 16.5 feet.

But here’s one welcome change: the $1.5 billion rehabilitation of the Herbert Hoover Dike around Lake O allows the Corps to safely retain more water in the lake than in the past. This, plus a commitment to greater flexibility — soon to be formalized in the new Lake Okeechobee System Operating Manual, or LOSOM — has prevented large-scale discharges so far this year. The Caloosahatchee is getting some lake water, and advocates say this is fueling blue-green algae now festering in the estuary. But so far this year, we’ve seen nothing to resemble 2013, 2016 or 2018.

In late 2021 the Army Corps and South Florida Water Management District celebrated the completion of the $339 million C-44 Reservoir, designed to divert discharges from the St. Lucie; the C-43, which would divert lake water from the Caloosahatchee, is under construction. Unfortunately, the C-44 is still in operational testing mode and not fully functional after “seepage” was discovered; and work on the C-43 has been delayed after the SFWMD fired the contractor working on the project. The dispute has landed in court.

Then there’s the supposed “crown jewel,” the Everglades Agricultural Area Reservoir and stormwater treatment area under construction south of the lake. The 10,500-acre reservoir and 6,500-acre STA won’t be fully operational for another decade at least. But once complete, it’s supposed to take a big bite out of future discharges; the reservoir will reportedly have a capacity of 240,000 acre-feet of water.

But to put that in context: in 2013 the St Lucie got 671,067 acre-feet of water; the Caloosahatchee got more than 2.5 million acre-feet. And the EAA Reservoir won’t be able to operate at full capacity if phosphorus levels are too high to send water south to the Everglades.

As should be apparent, we need more land for more storage south of Lake Okeechobee. Unfortunately, few are pushing for this, focusing instead on the need to fund projects already approved — projects which may help but won’t eliminate the threat of another lost summer.

There may be no quick fixes, though some conservation groups like the Florida Oceanographic Society say agricultural operations could be required to hold and treat water on their own land, freeing up space in the STAs for lake water.

And if space were available in the STAs, the lake level could be reduced prior to the wet season by sending water south rather than east and west.

“Until our state makes a commitment to begin lowering Lake Okeechobee at the start of the dry season by sending water south into the STAs, we’re going to be in perpetual storm watch, wondering it this will be the week or month toxic discharges get sent to the northern estuaries,” said VoteWater Board President Blair Wickstrom.

And that’s why we must keep pushing for change. Lawmakers have thrown billions at clean-water projects since 2013; that’s good and, to the extent those projects are effective, it must continue. But the goal isn’t to merely slow the discharges; it’s to stop them, once and for all — and to make 2013, 2016 and 2018 the last “lost summers” we’re forced to endure.